If it weren't for the gold!

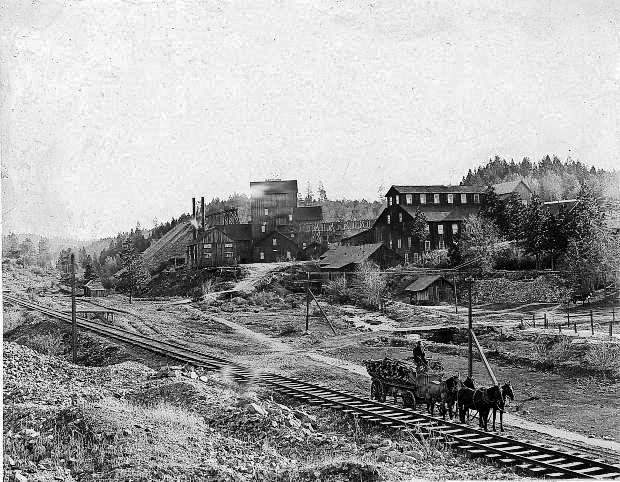

This is a story about an iconic company in the television broadcast industry, that took the name of a town, and eventually left and took the name with it. If you are an American Football fan you might recall the story of the Cleveland Browns. In 1996 the owner of the team announced the team was moving to Baltimore. Eventually the town fought and won the right to keep the Brown's name, while the team left town and took the name of the "Ravens." In this story the company took the name of the town with them and have currently settled in a place where 99% of the folks have no idea of the company's original reason for having the name that it does.The first half of the book answers that question, that there's a small town in northern California, and if you work in the technical or production areas of the television industry anywhere in the world, you know the name of the town. You probably wouldn't know it as a place, but as a vendor of high–end television production equipment. The building below is the last vestige of the Grass Valley Company remaining in the town of Grass Valley.

The Grass Valley Company started what became the greatest concentration of high–end video manufacturing in the world. At one time, but no longer, the area had the highest population, per capita, working in the industry than anywhere else IN THE WORLD!

This is a place today that still has almost two dozen companies that compete in the industry.

The building happens to sit on a hill that is riddled with mine shafts. The whole area is infested with these now abandoned shafts. Gold is what the town of Grass Valley, along with the adjacent town of Nevada City, grew up on.

As we will see the mine shafts that are hidden deep below this building were owned by a man who would inadvertently set into motion a series of events that would cause the germination of that cluster of high–tech endeavors that prevented the towns from becoming a backwater after the gold mining ceased. The secondary industry, lumber, was also in decline by the 1950s.

The towns, which still today sit two dozen miles from the nearest interstate, would be stops for people on their way to somewhere else if not for a few unlikely events. While the town's shops, and bed and breakfast establishments would be quaint, and its art colony probably still thriving, the towns would not have played a part on the worldwide stage as they have, and to a slightly lessor level, still do today.

It took gold, not because electronics uses the material, but because the owner of a local mine laid the seed for all that followed. The area is littered with these mines, from extremely large, to holes in the ground. All because a mine owner, who happened to own the very mine that this building sits atop, was convinced that the area needed a new "modern" hospital. The building of that hospital, never used as a hospital, a casualty of WWII, started a cascade of events that turned the mining and lumber town into a mini high–tech mecca.

The second thread to the story started down in the bay area. What became a very large defense contractor, and an early founding entity in what became Silicon Valley, was founded by a Stanford alumnus, who decided to escape the area. He decamped and took a small sapling from this company and planted it in Grass Valley. Why there? Because of what the mine owner had begun.

That entrepreneur enticed another Stanford alumnus of the same cloth, to join him up in the Sierra foothills. This second Stanford alumnus formed a company that allowed a mini "Fairchild effect," like the one that happened in Silicon Valley, to be replicated in Grass Valley. A high–tech eco–system sprung up in the area. One result was the first gaming cartridge console from Atari. The R&D was done in Grass Valley.

The original company that "started it all" in the area, to quote a Fairchild Semiconductor boast from the 70s regarding Silicon Valley, was bought and sold six times, so far.

For the first few years of its life the "Group" as they proudly referred to themselves as, cast about for a reason to exist. The company that started "video valley" as some have called it, the Grass Valley Group knew nothing of video when they arrived in town. The small company had come to the area from the east. Grass Valley Group, or GVG, to this day is still referred to as the Group by many old timers, even though the Group was dropped from the name long ago. The Group very well could have had Stanford or even Fresno before the word Group.

Then an ally with an ABC owned San Francisco TV station, suggested that if they made some refinements to a video distribution amp, ubiquitous in television stations, that they might be able to compete against the likes of the then giants RCA, and GE among others. Some thought that idea preposterous, but in short order they produced their first model. From then on when opportunity sprang up, the group was able to respond quickly to each new avenue presented to them.

Their big early benefactor, ABC, the third in a three–way network universe at the time, wasn't able to get a piece of equipment they needed for an upcoming large event and turned to the Group in desperation. The network asked the Group if they could produce a "Proc Amp." Dr. Hare, the Group's founder, president, and chief engineer's first response was "What the hell is a proc amp?" Within 10 days they had a working prototype that was even in a case. That was the Group's way early on. Respond quickly to opportunity. As the story will show, years on, the company did not always keep that in sight.

From the products that were rudimentary processing equipment used by television broadcasters, the group produced more exotic and complex systems that moved the company up the professional television broadcasting food chain. They pushed product lines that had been pioneered and developed for twenty years by the industry leaders of the day and soon had the entrenched players following Grass Valley's lead in innovation.

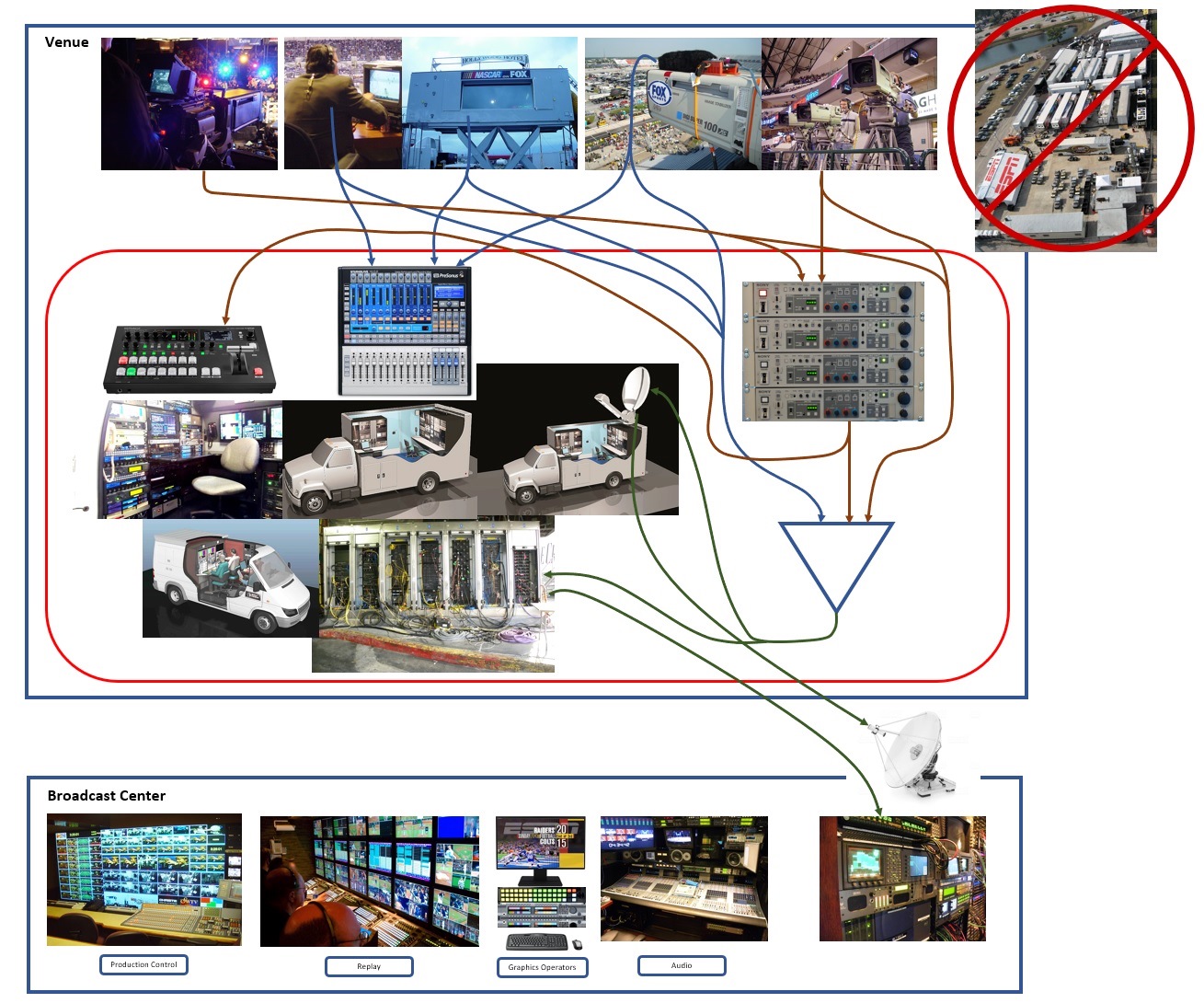

The Group became the dominant player in video production switchers. These are devices that allow all the layers of graphics, effects, and a myriad of sources to be integrated into a complex mosaic of video. Oh yeah, this is all done in real time while the newscast, sporting event, or entertainment show is happening.

By the mid 1970's the Group had enough of the high-end video market that one of the props used to destroy Princess Leia's home planet of "Alderaan" in the first Star Wars film, was a video 'fader bar' on a Grass Valley 1600 video production switcher. This was the second generation of video switcher production equipment developed by the Group. The Group is still a dominant player in this market.

For over six decades television's technical and production bigwigs made the trek to this town to collaborate with the technical gurus that had congregated here. The Group affected the world, and the world affected the Group. They were on the stage with the mighty and powerful.

For over six decades television's technical and production bigwigs made the trek to this town to collaborate with the technical gurus that had congregated here. The Group affected the world, and the world affected the Group. They were on the stage with the mighty and powerful.

They were pushed around by the likes of George Soros. They cooperated with and then competed against Sony. In some ways Sony and the Group were kindred spirits, in that both started out not knowing what to produce, with forceful founders, and the early embrace of semi-conductors. Both made large marks on the arenas they played in.

The Group was the sturdy Oak for many years, that only grafted a spin off once, but dropped acorns all around it, and the lone tree, became a stand of trees. A mini "Fairchild Effect" to what happened down in Silicon Valley.

As we will see many improbable things had to happen for the Group and other high-techs that sprung up around it to have occurred. We mentioned two dozen miles from the nearest interstate, how about 60 miles from the nearest commercial airport.

Maybe the most improbable thing we will see in this story is that the Grass Valley name, as a company, still exists. As mentioned, the company had been sold and spun off a half dozen times, and it now has DNA from almost three dozen companies! At times it was only a division of companies many times its size. Through the various ownership changes it was merged with other "best of breed" companies. Yet it is the Grass Valley brand that is still standing. Maybe a bit nicked, as its logically historically green GV logo, is now magenta.